Hidden Pain, Hidden Treasures

In the springtime, my mother would bring lilacs inside, big armfuls of them, and put them in deep burgundy glass vases. Their fresh and wild scent filled the house, wafting through screen windows that had been hand-changed, from storms to screens, only weeks before.

In the springtime, my mother would bring lilacs inside, big armfuls of them, and put them in deep burgundy glass vases. Their fresh and wild scent filled the house, wafting through screen windows that had been hand-changed, from storms to screens, only weeks before.

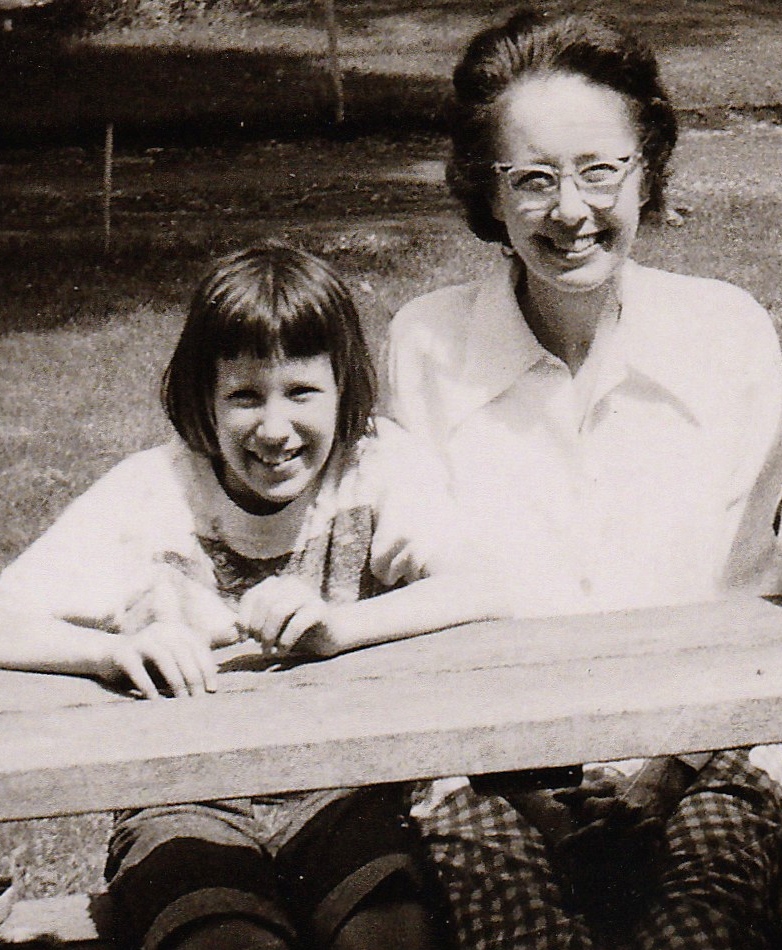

And maybe that’s why they smelled so good. In Minnesota, springtime is earned, not taken for granted. But in the spring of 1965, as killer tornadoes and record floods ravaged Minnesota, I breathed in that sweet combination of lilacs and mother-presence for the last time. In the fall, when she was fifty-three, and I was eleven, she died.

I should have known it was coming. Everyone else did, for she’d had cancer for six years at that point. Not that the word was ever mentioned—it wasn’t, at least when I was around. There were things you didn’t talk about with children, and death was one. Clearly she was sick: in and out of hospitals, oever fifty radiation treatements, many prescriptions to fill…but the word “cancer” was never used. I finally understood her reluctance to talk about it when I had children. I would not have wanted to have that conversation, either. But still she should have.

So she did some things wrong…but much more right. And at the top of those things that were right was her faith. There is an old saying: “Faith can’t be taught; it must be caught.”

I caught it. Somehow in the darkness that must-not-be-mentioned, I sensed the presence of God nearby. I was never alone. And I saw how prayer and thinking outside oneself was both a holy expression of God’s love, and a route to survival.

She had friends, lots of them. And she would visit three in particular. Somehow I always wound up along on the visits; I’d like to think I was noble, but it was probably because I sensed she was dying and didn’t want to let her out of my sight…thinking that if I was there, nothing bad would happen.

One friend of hers was Gladys, a blind, crippled old woman who lived in a tiny, dark, urine-scented shack on Lake Minnetonka. My mother would turn open the windows, push back the curtains, chat with Gladys, and empty the coffee cans that the old woman used for toilets. And it wasn’t because of some macabre “let’s visit the lonely.” It was because she liked Gladys and Gladys liked her. I, on the other hand, liked the sun and lingered outside, anxious to escape the smells and darkness within.

Then we’d go see Posie, a woman in an iron lung. Because of polio, she was sentenced to lie forever within a great silver beast, dependent on it for every breath. Always on her back, she could only see us by looking into a mirror over her head, the same mirror we also used to make eye contact with her. Seeing someone live in a steel tube was staggering for a nine-year old. Yet she smiled. She did more than smile. In the midst of what must have been agony, she had joy.

And then there was the mother on the steep hillside of Christmas Lake, whose twelve-year old son was being laid waste to by cancer. I admired Kirk’s escalator chair, built into the hillside to ferry him down to the lake so he could enjoy the water. Yet only a few years than me — he was dying — which is why had no strength to run down to the lake. We returned time and time again; I knew that Kirk’s mother somehow leaned on my mother, for they were both confronting terrible probabilities. They needed each other.

Catching the faith. I never knew it at the time, yet examples of faith were being tossed to me all the day long.

But what about the night? What about when all comes to a stop and the loved one is gone? What then?

No one speaks to that sense of loss better than German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in Letters and Papers from Prison:

“It is wrong to say that God fills the emptiness. God in no way fills it but much more leaves it precisely unfilled and thus helps us preserve—even in pain —the authentic relationship. Furthermore, the more beautiful and full the remembrances, the more difficult the separation. But gratitude transforms the momory into silent love. One bears what was lovely in the past not as a thorn but as a precious gift deep within, a hidden treasure of which one can always be certain.”

Precious gifts deep within. Hidden treasures. Gifts for a lifetime. L’chaim!